The first two talks I saw yesterday were about ongoing work at the Altiplano Volcanic Complex (APVC) in Chile. Above is a Flash Earth image of the area; click the pic to embiggen or

explore further here. I'm certain the image is in the right general area, but I didn't get enough information to know for certain whether it actually covers any of the specific sites under discussion.

I was uncertain exactly what to expect from these

GeoDay talks, but they are essentially grad students presenting what they're doing in their research; most have done some of the work, but the focus is not on presenting and defending results and conclusions. Instead, the focus is on the how and why: why is the research relevant or important, and how will it be carried out? After watching eight of these 20-minute presentations, I came away favorably impressed with the format's ability to give students an opportunity to practice their public speaking and presentation skills in a relatively low-risk setting.

The first talk was by

Stephanie Grocke, (The links I will attach to each name will take you to the relevant abstract) who is examining melt inclusions to determine whether there was a volatile gradient in the pre-eruption magma chamber. Her talk was the first to really strike me with the realization of how far geochemical measurement techniques have advanced over the last 20-25 years: the resolution is pretty incredible to me. Melt inclusions are tiny bits of original melt that have been isolated within crystals since before eruption, and thus contain a record of the magma as it was originally composed in-situ. One example she showed looked from the scale bar as if it was approximately 100x200 um, or 0.1x0.2 mm... for those who want their

dimensions in English, that's about 4 by 8 thousandths of an inch. And that was a large one. The idea that you can accurately measure the composition of anything that small is amazing.

Her hypothesis is that volatile components (CO2 and H2O) were more abundant in the top of the magma chamber, driving the initial Plinian eruption style. Later in the eruption, a decrease in volatiles led to a decreased velocity of the eruptive column, and thus to the column's collapse, resulting in a widespread (and startlingly thick!) ignimbrite deposit. Stephanie visited the area last November and collected samples, and is now in the midst of (what looks to me like) the mind-numbingly tedious process of separating and preparing quartz and feldspar crystals with pristine vitreous inclusions- there's a set of criteria for what constitutes a satisfactory inclusion for analysis- for later compositional analysis. It turns out Stephanie moved to Corvallis from very close by the area from which I moved to Corvallis, within 20 miles or so!

The second talk was by

Casey Tierney, working in the same general area, the APVC, but on domes rather than ignimbrites. The task he has set himself is to analyze accessory minerals- notably zircon and sanidine- to get at the thermal history of the magma chambers that erupted to form the domes in question. Zircon starts crystallizing at about 850 C, so the innermost zones of that mineral would record the age at which the magma first cooled to that temperature. Sanidine remains diffusive with respect to Ar essentially until it erupts, so its age effectively measures the eruption's date. The difference between the U/Pb age from zircon and Ar/Ar age from sanidine gives a (minimum?) residence period for the magma in the magma chamber. And again, I'm sort of shocked that there is enough confidence in the accuracy and resolution of these dating techniques to meaningfully get at periods that are certainly going to be small compared to the decay times involved in those radiometric series.

Related questions that can be addressed with residence time include magma source; was it one batch of magma, or were new batches added during the residence time? Also, thermal history; if new batches were added though time, it's possibly a magma chamber could be rejuvinated. Otherwise, one could conclude that the system is slowly cooling. Based on other studies of similar dome complexes in the Andes, Casey provisionally expects to find this field was a single source, and that it is slowly cooling.

I'm going to skip the geography presentations; I found them interesting, but I simply don't know enough to meaningfully discuss what I saw, and worry I'd make a hash of them. If you're interested, you can go back to

the GeoDay post and read the abstracts. Certainly the topics are of interest to geo-literate people, but they're far enough away from my knowledge base that I'm hesitant to say much.

At 2:00,

Wendy Kelly presented her plans to develop an interpretation training manual for Shenandoah National Park and its employees. To tease that apart a little further, the document is intended to guide and educate rangers and other staff who have frequent contact with the public they serve on the geology and geologic history of the park, and how to help the public understand and appreciate that geology. Wendy's talk focused primarily on the logistics of developing the manual, not on laying out the current knowledge of the geohistory of the area- this might have been a little disconcerting to the "real" geologists in the audience, but was actually kind of a relief for this science educator to see.

As Wendy pointed out, this issue really is one of interpretation- of finding ways to translate complex concepts scientists become accustomed to tossing around with shorthand terminology to language that the general public can understand.

As an offhand example, let's take the phrase "arc-continental collision." To a geoscientist, each of those words carries an abundance of information and presumed assumtions: arc= a chain of volcanoes arising from subduction, partial melting and resultant volcanism, typically in the form of evolved, more silica-enriched melts. Volcanism is often (though certainly not always) in the form of stratovolcanoes. Continent= thickened crust with an overall granitic-granodioritic composition; central (cratonic) area is largely inactive, but may alternate between epicontinental seas and periods of erosion, resulting in a thin (compared to total crust thickness) veneer of mostly horizontal, undisturbed, sediments. Edges may be active- undergoing interactions with adjacent plates (think US west coast), or inactive- attached to (and actually the same "plate"as) adjacent oceanic crust (think US east coast). Collision: two plates collide with each other, typically creating an episode of mountain-building and deformation, and possibly associated volcanism. Afterward the two plates are attached, and will share a common geologic record- though rocks predating the collision may have wildly disparate histories. Now look back at that paragraph. Three simple words, "arc-continental collision"- which also have their own, different, commonly understood colloquial meanings, further confusing the task of interpretation- carry an enormous amount of assumed meaning in a conversation between geologists. And it would be easy for me to expand that paragraph many times to clarify other meanings and assumptions of implied meaning.

But to a member of the general public, none of that shared understanding is there- at least you have to start with that assumption.

So the task Wendy has at hand is to "translate," via careful choices of language, graphic representations, analogies, metaphors and similes, an extremely complex (therefore interesting) geologic record into terms park employees can understand well enough that they can do the same for the public. Not an easy task, but one I'd love to tackle myself.

Overall, her approach is to have four sections: a broad overview/sketch of Appalachian geohistory, a more detailed technical regional overview that delves into the finer points, then a parallel pair of sections at the local level: an overview of the geological, biological and cultural history of the park area, and a technical examination of the historical details.

I had two minor quibbles: Wendy stated that the general public is not terribly interested in geology, and went so far as to say they're afraid of science. I disagree. I've found that the vast majority of people I've interacted with love to learn about the history of the landscape and materials that surround them, but you do have to approach the subject at their level. That can vary tremendously from one person to another, of course. Over the last 20 years, I have come to believe that

all human beings have an innate desire to understand the world around them- that's our competitive edge. In terms of physical prowess, there's not much we're terribly good at: we're not specialists. Our prowess is in understanding and predicting behavior in our surroundings, and manipulating those surroundings in ways we believe will benefit us. From that perspective, you can see why I believe it's an innate tendency. What people are afraid of is not science, but that learning science will be more work than it's worth. An interpreter's or educator's job is to get the learner past that fear.

The second quibble is that there was no discussion of an evaluation plan. This is a geology degree, not an education degree, but it's troubling (though very, very common) that these things are produced and put out there with no plan to judge whether it had an effect, or even whether it reached its intended target audience (in this case, visitors to Shenandoah NP).

The final geology presentation I saw was

Jennifer Cunningham's on developing better models on trace element partitioning in clinopyroxene. Basically (OMG, awful geopun there... completely unintentional, mind you), clinopyroxene is a very important component of mafic igneous rocks, and having better numerical models of how trace elements partition between those mineral grains and the rest of the melt has the potential to allow better geothermometry (estimating temperatures of petrogenesis) and geobarometry (estimating pressures of petrogenesis).

I have an enormous amount of respect for a student willing to cull data from literally hundreds of articles from the geologic literature (and go through hundreds more only to find they don't have relevant data), then go through the further, and perhaps even more tedious, process of developing a better fit algorithm for something in the range of 15-20 trace elements. That said, this is a project I would never want to do, personally. It could be of enormous utility, but I hope she has a strong background in math and especially computer science. She showed a flow diagram illustrating her approach, but didn't say much about how she would actually develop and tweak her models. From my perspective, not knowing much about computer science or statistics, the only practical way I see is having a computer run through many iterations for each element, finding the best fit for the parameters of interest. She may have more streamlined methods to work with, but I suspect this problem wouldn't even have been possible at the time I graduated; it would have required too much computing power. As it was, this one was right at the edge of what I could comprehend. The thought of the problem is fascinating to me, but the thought of trying to actually tackle it is frankly horrifying,

So there you have the geology portions of the GeoDay afternoon. I enjoyed myself, though I get a little anxious being surrounded by large numbers of people I don't know, and was happy to return to my dark little corner in my favorite coffee shop.

From The Washington Post, trying to figure out how medieval map makers achieved the accuracy they did. No one knows. (But we're pretty sure it wasn't aliens. No, seriously. It wasn't.)

From The Washington Post, trying to figure out how medieval map makers achieved the accuracy they did. No one knows. (But we're pretty sure it wasn't aliens. No, seriously. It wasn't.) Rogue River-Siskiyou National Forest at the Botany Photo of the Day, found in Julia's shared items. Sigh... plants and rocks and falling water... sigh. I love Oregon.

Rogue River-Siskiyou National Forest at the Botany Photo of the Day, found in Julia's shared items. Sigh... plants and rocks and falling water... sigh. I love Oregon. A recently created Hubble Picture of the Week site at ESA, via Bad Astronomy.

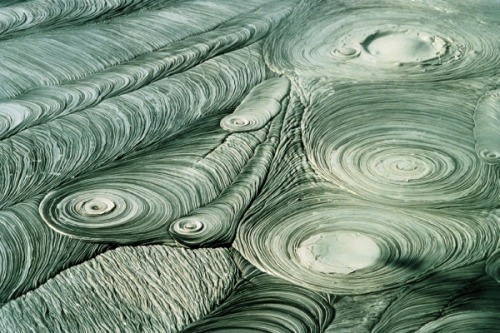

A recently created Hubble Picture of the Week site at ESA, via Bad Astronomy. A lovely abstract in New Zealand mudpots; Geology Rocks.

A lovely abstract in New Zealand mudpots; Geology Rocks. Textural and mineralogical characteristics of unpronounceable ash at Eruptions.

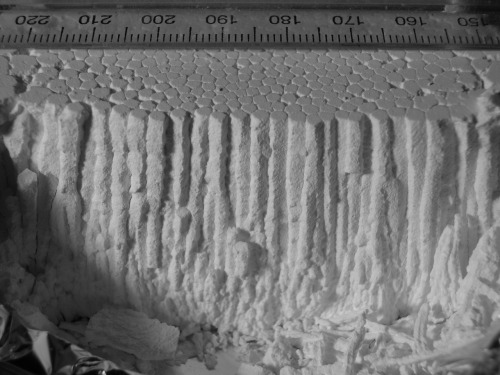

Textural and mineralogical characteristics of unpronounceable ash at Eruptions. Columnar basalt model with a common kitchen material and water + time, via Geology Rocks. Add coloring for more realism?

Columnar basalt model with a common kitchen material and water + time, via Geology Rocks. Add coloring for more realism? California is a world in itself; Hollywood's map of location locations, from Strange Maps.

California is a world in itself; Hollywood's map of location locations, from Strange Maps. That's an animation of the first visible wavelength images of the Saturnian Aurora.

That's an animation of the first visible wavelength images of the Saturnian Aurora.