I realized that I should have posted an argument for just why geology undergrads should be trying to find time to read geoblogs in yesterday's post. There are a lot of reasons.

Interest: Most geologists are truly passionate about their subject area- more uniformly and more so than in any other field of which I'm aware. Perhaps I'm biased and/or naive, but I don't think so. The more you delve into it, the more fascinating it becomes. The more you understand, perversely, the more you realize you don't understand, but the more you want to understand. Blogs offer bits and pieces freed of academic structure- which I believe is a necessary part of getting the edumaction (The structure, to be clear)- and are pressure-free. None of this is going to be on the final. On the other hand, you might accidentally learn something that does show up on a test eventually. Geobloggers do this because they're interested, and it can be infectious.

Enthusiasm: Like interest, geologists and geobloggers just glow with enthusiasm, and that too can be catchy. When you read a post that comes across as breathless, you want to go see that spot. You want to share that experience. You want to solve that puzzle. I could also call this "motivation." We all want to feel that way. See Dana's Rosetta Stones post from earlier today; she really wants to visit that beach... don't you? (I actually have visited that beach a number of times in the seventies, sadly before I knew what I was looking at.)

Support: Everyone has times they're down, or times when something just seems overwhelmingly confusing. I'd say we as a community are extremely supportive of others. We empathize with the plights of students- geology students in particular. I can't offer much beyond empathy to, say, a physics student. But for undergrad geologists, I can be very helpful. I can't tell you more accurately than "a couple dozen" the number of times people have been in here studying something geology related. Geologic terms to me are like hearing your name spoken in a crowded, noisy room. My ears perk up, and I want in on the conversation. I'm not rude about it, but I definitely make my interest known, then offer my help. There have been study groups that return regularly, hoping I'll be here (I generally am). Same thing online. Twitter is even better than blogs for this- you can crowdsource a question, and often have an answer (or a PDF) in minutes. There have even been a few times when I've written extensive posts discussing complex issues that don't have single or simple answers (for example).

Learning: Whether it's a concept you're unfamiliar with, or a location you decide to visit later, one inevitable consequence of reading geoblogs is that you're going to learn something unexpected. As a student, you should jump at every low-cost opportunity you get for learning. And it just doesn't get lower-cost than blogs.

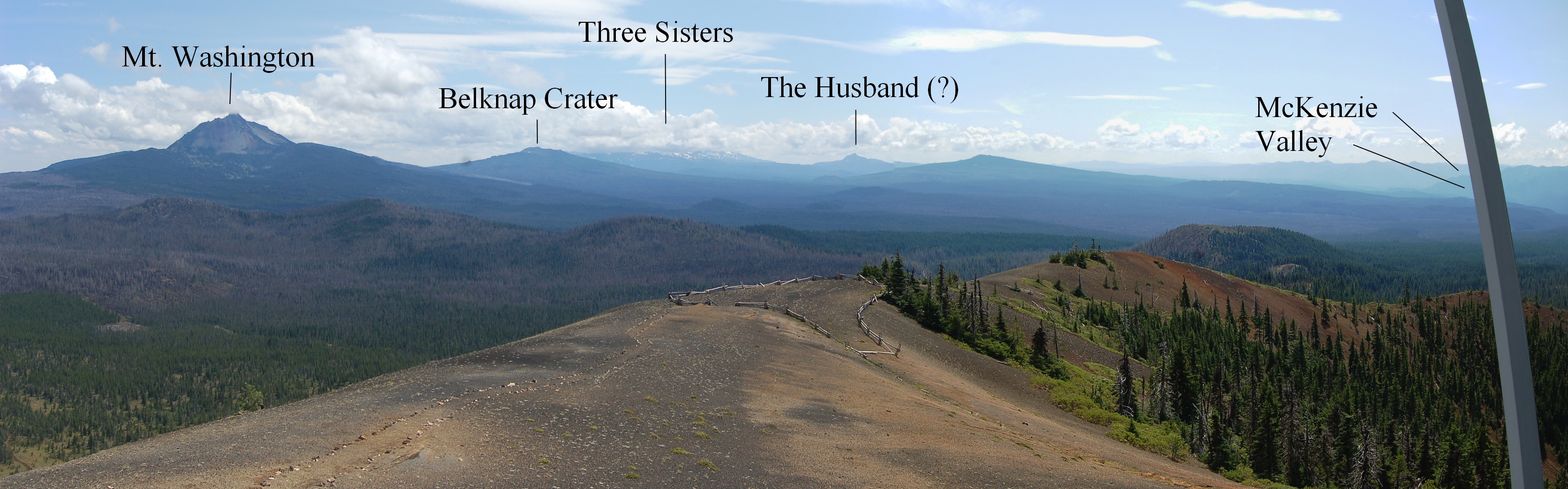

Contacts and community: Every field relies heavily on who you know. This is not always a good thing, but it's a fact. And often, it is a good thing. When Callan Bentley's student Aaron Barth moved to Oregon to attend OSU, the former sent me a note, and I suggested a number of places in the Eugene area (where he lives) to the latter. And when Dana came down in July, we took him along on a field trip to the Quartzville area. When Anne Jefferson and Chris Rowan were out earlier this summer, I spent a couple of days showing Chris around the Neogene sediments of the Coast Range. And if I was to visit the stomping grounds of any number of geobloggers, I know exactly who I'd go to to get oriented to local rocks.

Communication: One aspect of my undergrad career that might have been problematic if I personally (not the curriculum) hadn't taken steps was that of communication. It baffles me how many people think clear, low-error communication isn't important in science classes. Communicating well is perhaps even more important than core competencies; if you can't effectively pass your knowledge on to others, what's the point of generating it in the first place? Geobloggers provide numerous daily examples of clear, effective (and often, delightful) communication every single day. I also think that reading well-written material is an important component of learning how to write well. Writing poorly can kill a career. Everything from getting grants to writing company reports or peer-reviewed articles depends on your communication skills. The time to get those down pat is during your undergrad career.

Models: Every geoblogger provides a model I would encourage you to emulate: start a blog! It's fun (if not always easy), and it takes exactly the amount of time you want it to. Want experience talking about (and thinking about and tentatively solving problems in) geology? Start a blog. Want to show off photos from a field trip? Start a blog. Want to polish up your writing skills? Start a blog. Want to be a part of a supportive community? Start a blog. Want a place where you can get thoughtful feedback and commentary on a geoconjecture? Start a blog.

Geoblogging and geoblog reading: It really is all that.

Is This Your Hat?

11 years ago