Our time at the coast last May was misty, cloudy, gray, windy and cold. It was gorgeous and fascinating, but unpleasant to be out in it for any length of time, especially if the location offered no shelter from the wind. As a result, many of our stops were quick and cursory. Here we were so exposed that we walked up to the edge, snapped a few photos, then headed quickly back to the car. If you enlarge the photo, you can see the leftmost stack is actually an arch, and even without enlargement, the biggest, near the middle, bears an amusing resemblance to a cartoon drawing of a whale. If it's not called "Whale Rock," it ought to be.

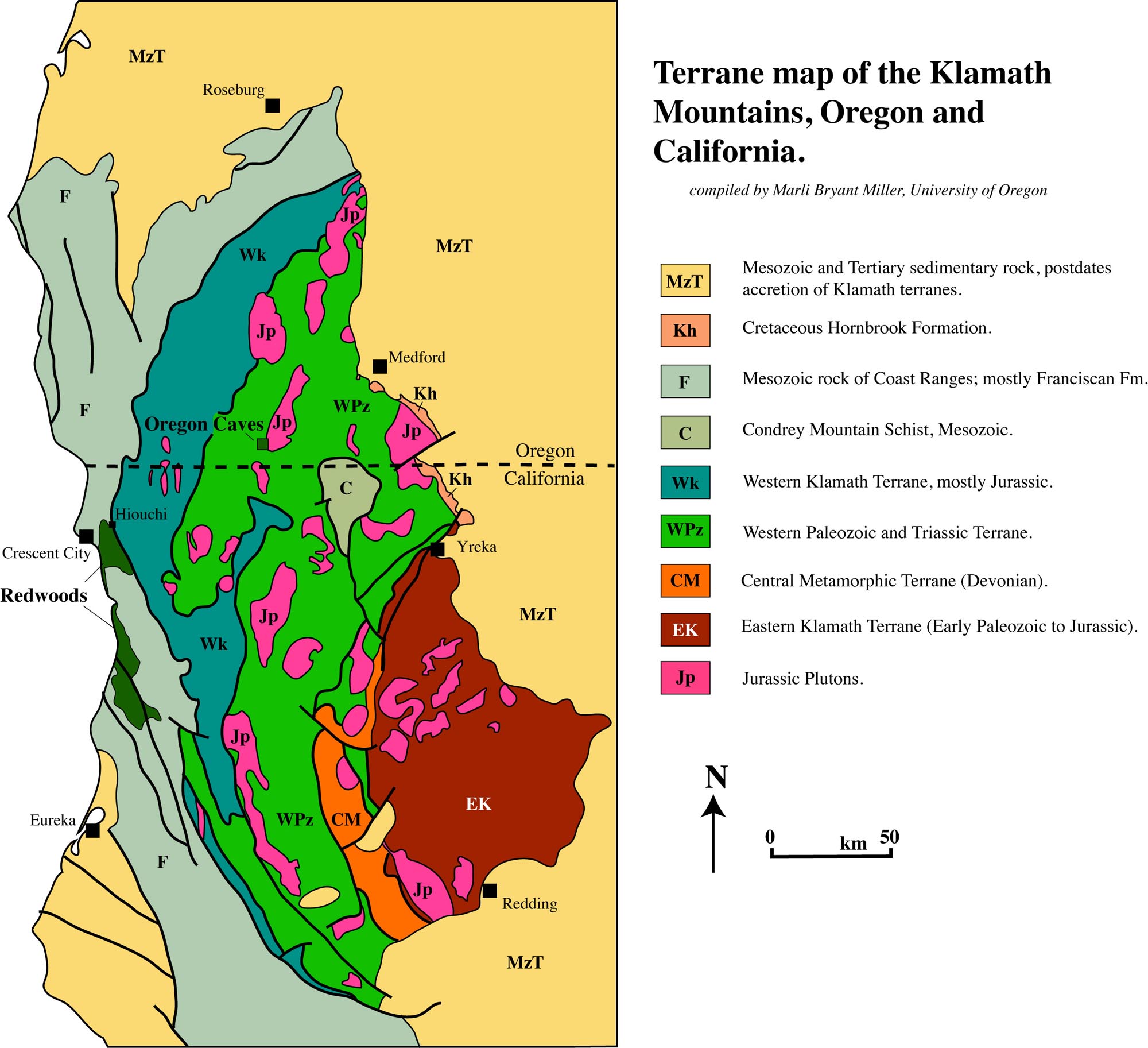

If I had to guess, I'd say the sea stacks in the distance are likely also Otter Point Formation, but lithologies change so fast in the Klamaths- especially east-west- that it would be just a guess, and not a very useful one. The reason I say "especially east-west" is that that's the general strike of the structure. Cross a fault, and you're into rock from an entirely different environment, of an entirely different age, with an entirely different history. And even without crossing a fault, the rocks are severely deformed and folded, again with the axes of the folds striking generally north-south. This means as one travels, the stratigraphic position can change very rapidly, even in the absence of faults. As I just told another Interzone denizen, "Klamath geology makes my brain hurt."

Map image by

Marli Bryant Miller. To be clear, this is extremely simplified; each of these terranes have their own subdivisions, and many are themselves composed of two or more subterranes, which accreted before docking with North America.

Photo unmodified. May 7, 2013.

FlashEarth location.