This post is dedicated to Dana Hunter, who seemed particularly unsettled by my endless questions when we went to Marys Peak and the coast last fall. I'm going to spend five long days with her very soon, and thought she at least deserved to know that my questions are not intended to be "tests." They are, in fact, much more subversive and manipulative than that. Fair warning though: knowing what I'm doing and why will not free you from the effect I describe. ;)

There are two main reasons teachers ask questions: assessment and motivation. Assessment can either be formative (trying to figure out where students are in terms of knowledge and understanding, so one can more effectively and efficiently guide them to your goals and objectives) or summative (trying to determine if they have indeed arrived at the set objectives). Motivation in this case means that students are more likely to mentally engage with a topic at hand if they are frequently and regularly asked questions... and particularly if they

expect to be asked questions, and

expect to be obligated to answer them.

One of the reasons I left teaching was the disgust I feel with our society's obsession with grades. Is that the only reason we have to learn any more?

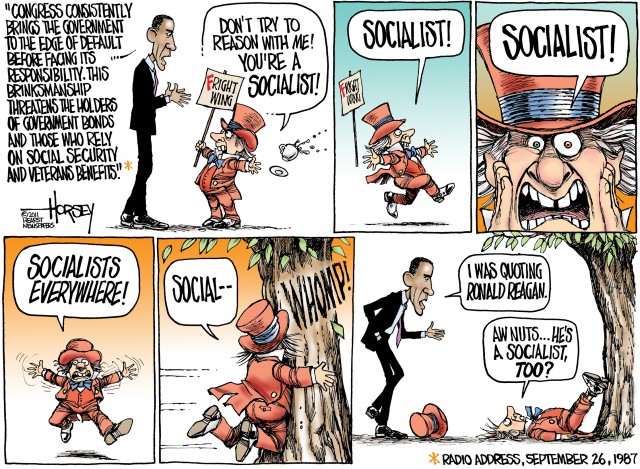

Well, for some, yes: "You teach a child to read, and he or her will be able to pass a literacy test." -Townsend, Tenn., Feb. 21, 2001. BRAAAPP! Sorry, Dubya, you get to start over with grade one. So the idea of questions as "tests," while necessary, an unavoidable component of traditional teaching, important, justified, what have you, is just distasteful and offensive to me. I rarely ask those sorts of questions.

I sometimes ask questions to figure out what I need to clarify. I was going to tell my hipster geology gag about thalwegs to a student in environmental science, but asked first if he knew that term. (he did, and loved the joke). So formative questions can be quite useful to figure out what background you need to cover before getting to the meat of the subject at hand, and I ask these sorts of questions fairly often.

But it's the "motivational" questions I really love. Educational research has consistently shown that it's more about the frequency and expectations students have for questioning than the cognitive level, difficulty or complexity of the questions. Obviously, for advanced learners (i.e. upper level undergraduates and up) some of the questions need to be demanding. But the expectation that there will be questions, and that the learner will be expected to give some kind of response, do the most to keep the mental faculties engaged.

There's also a side issue which I think is best claimed as a matter of personal opinion and educational philosophy- I don't know that I've read the perspective I'm about to present elsewhere.

I view questions as a sneaky, subversive and somewhat unfair- though completely ethical- opportunity to issue imperatives. If I say "Describe that outcrop," and do it often enough, I will come to be seen as abrasive and even dictatorial. On the other hand, if I wave and point at an outcrop, and with a smile, ask "What do you see?" then wait... The student has been given almost no guidance, and is generally not sure what specifics I'm after (because more often than not, I'm not after any particular thing[s], specifically), and may not even be sure where to start, yet there I stand, bemused grin smeared across my mug, waiting... This is a powerfully motivating situation for students. Why? Perhaps it's fear of failure, or the fear of looking diminished in the eyes of an instructor. I'm honestly not sure, but it's a very real feeling that I have experienced myself many, many times. In my own case, I think it's mostly a matter of living up to my own expectations for myself ("C'mon, dude, you oughtta know this one..."). But I recognize that widened-eye flicking of students' minds racing when I see it. I feel a slight pang of guilt sometimes, because I don't like that feeling of cognitive near-panic either. Still, I know that working through it can lead to some powerful learning experiences, so in my estimation, it's worth it.

So when I hand you a rock or point out an outcrop, and ask an innocuous question like "What do you see," or "How do you suppose that might have happened," or "Why is that growing there," or any of hundreds of other open-ended questions for which there is not and cannot be a single "right" answer, I'm not testing you. I'm telling you to look and think. Because questions are an imperative way to do that in a much more effective and much less irritating manner than pointing at an outcrop and saying "Look! Think!"

Or if you'd like the blunt version, I'm messing with your head.

I'm a teacher at heart. That's what I do.

In honor of a past employee who's visiting this weekend, Interzone is running as a special the breakfast he liked to prepare for himself when he worked here. They haven't run a special in quite a while, and as much as I love the weekend Super Burrito, I gotta give this a try. I'm substituting an everything bagel for the toast. Should be showing up any minute now...

In honor of a past employee who's visiting this weekend, Interzone is running as a special the breakfast he liked to prepare for himself when he worked here. They haven't run a special in quite a while, and as much as I love the weekend Super Burrito, I gotta give this a try. I'm substituting an everything bagel for the toast. Should be showing up any minute now...