Fanfare for the Common Man- the tempo, uh, changes at about 3:30.

Miscellaneous thoughts on politics, people, math, science and other cool (if sometimes frustrating) stuff from somewhere near my favorite coffee shop.

Saturday, January 19, 2013

Saturd80's: Emerson, Lake and Palmer Edition

Yesterday, I tweeted, "Oddly, I was introduced to Aaron Copeland's music by Emerson, Lake and Palmer. (Fanfare for the Common Man)" Now I doubt I reached my late teens without hearing music by Aaron Copeland, but that composer has a very distinct "American classic" sound, which at this point I can pick out pretty easily and confidently. But it was Emerson Lake and Palmer that brought him and his style to my attention. "Fanfare" can, and often does, give me goosebumps to this day, and I think it's spirit is demeaned by using it for things like televised sports.

Fanfare for the Common Man- the tempo, uh, changes at about 3:30.

A classic, their own composition, Lucky Man:

And like many other bands, they also covered Peter Gunn- their version is quite distinct:.

Fanfare for the Common Man- the tempo, uh, changes at about 3:30.

Friday, January 18, 2013

Geo 365: Jan. 19, Day 19: Not Quite Normal Normal Faults

Okay, it's not Jan. 19 yet, but I'm very pleased with the results of my puttering around today, and I can't wait to share. So here we go.

This is a panorama, stitched together in Hugin, of two shots of the same set of normal faults shown yesterday. Yesterday's photo, nice as it is, was mostly to give a sense of scale. Here there's no scale, just the gorgeous faults nicely highlighted by the great contrast in the colors of various sediments.

Now I presented this yesterday as "Basin and Range," and that's still my preferred explanation for this faulting. It's in a logical place for that to be true, and the mode of offset- normal, where the blocks on the upper side of the fault plane have moved down with respect to blocks on the lower side- is what I'd expect to see as we crossed out of Basin and Range onto the edge of the Cascade platform. But...

Here's an annotated version:

With the exception of two minor faults in the lower middle, marked in red, all are normal in offset. And aside from a couple of the larger ones, most of them don't seem to go all the way through. I was pondering this when I was there with Dana, but was A) kinda confused myself; B) not really confident in what I thought I was seeing, and C) really didn't want to confuse her. My suspicion is that I need to think about syndepositional deformation- faulting taking place as, or shortly after, the sediment was deposited. Now, soft-sediment "brittle deformation" is kind of a contradiction in terms, but I've seen it a number of times, both on the Oregon Coast and in glacial sediment in Ontario, Canada, so I know it can happen. (Followup: oh, yeah, also here.) So the answer? I just don't know. It might be one, the other, possibly even a combination of both- for example a Basin and Range-related earthquake may have led to more extensive slumping and extension of a delta front than just the simple tectonism caused by itself. I'm not even sure getting my nose up on the outcrop would help- though being able to look carefully at just how exactly those smaller faults peter out might.

I will say, spending an hour or better, squinting at my computer screen, and painstakingly highlighting the faults, while tedious, definitely convinced me that this is a real problem I can't just dismiss with a hand wave.

Photo unprocessed, other than stitching and cropping. August 18, 2011. FlashEarth location. (Cross-hairs on pull-out. The high tension power lines are the landmark to look for, here- this is the main conduit for taking Columbia River hydropower to California.) If you choose to visit this spot, please see Monday's safety comments; as I commented yesterday, we chose not to cross here. Just too dangerous.

Also, as a reminder, Blogger shrinks my photos somewhat, so some fine detail may be lost, even when you open them to "full size." I'm always happy to e-mail original copies for educational purposes. Followup note: I just checked, and at full size, the images above are 1600 x 640; the originals are 3297 x 1317- more than twice as big in linear dimensions.

This is a panorama, stitched together in Hugin, of two shots of the same set of normal faults shown yesterday. Yesterday's photo, nice as it is, was mostly to give a sense of scale. Here there's no scale, just the gorgeous faults nicely highlighted by the great contrast in the colors of various sediments.

Now I presented this yesterday as "Basin and Range," and that's still my preferred explanation for this faulting. It's in a logical place for that to be true, and the mode of offset- normal, where the blocks on the upper side of the fault plane have moved down with respect to blocks on the lower side- is what I'd expect to see as we crossed out of Basin and Range onto the edge of the Cascade platform. But...

Here's an annotated version:

With the exception of two minor faults in the lower middle, marked in red, all are normal in offset. And aside from a couple of the larger ones, most of them don't seem to go all the way through. I was pondering this when I was there with Dana, but was A) kinda confused myself; B) not really confident in what I thought I was seeing, and C) really didn't want to confuse her. My suspicion is that I need to think about syndepositional deformation- faulting taking place as, or shortly after, the sediment was deposited. Now, soft-sediment "brittle deformation" is kind of a contradiction in terms, but I've seen it a number of times, both on the Oregon Coast and in glacial sediment in Ontario, Canada, so I know it can happen. (Followup: oh, yeah, also here.) So the answer? I just don't know. It might be one, the other, possibly even a combination of both- for example a Basin and Range-related earthquake may have led to more extensive slumping and extension of a delta front than just the simple tectonism caused by itself. I'm not even sure getting my nose up on the outcrop would help- though being able to look carefully at just how exactly those smaller faults peter out might.

I will say, spending an hour or better, squinting at my computer screen, and painstakingly highlighting the faults, while tedious, definitely convinced me that this is a real problem I can't just dismiss with a hand wave.

Photo unprocessed, other than stitching and cropping. August 18, 2011. FlashEarth location. (Cross-hairs on pull-out. The high tension power lines are the landmark to look for, here- this is the main conduit for taking Columbia River hydropower to California.) If you choose to visit this spot, please see Monday's safety comments; as I commented yesterday, we chose not to cross here. Just too dangerous.

Also, as a reminder, Blogger shrinks my photos somewhat, so some fine detail may be lost, even when you open them to "full size." I'm always happy to e-mail original copies for educational purposes. Followup note: I just checked, and at full size, the images above are 1600 x 640; the originals are 3297 x 1317- more than twice as big in linear dimensions.

Geo 365: Jan. 18, Day 18: Basin and Range on the Roadside

A very, very nice horst, and a sweet little graben to its upper right, a bit up the road from the exposure I've been going on about since Monday. What with the Jersey barrier, the groin behind that, and busy traffic, we chose not to even try crossing here, but just took photos and enjoyed the fantastic faulting from across the road. I had been a little confused about what exactly was going on here, because I'd been under the impression the road was running north-south. Elsewhere, it mostly is. But along this stretch, where we're climbing up out of the Klamath Basin, to what I refer to as the "east side apron-" the flat apron of pumice and ash from explosive High Cascade volcanism- the road is actually running about NE-SW, so the angle to Basin and Range structure makes better sense. Still, I'm suspicious that this is not quite as simple and straight-forward as it looks... I'd *really* like to get up close and personal with this outcrop.

I had never stopped here before, and I don't think I'd even noticed how great this road cut was, despite having passed somewhere around 15-20 times over the years. It actually was a very fortuitous stop, because Dana had never seen Basin and Range consciously, so I was able to use the structures exposed here to introduce her to the structures we'd be seeing on a much grander scale over the following couple days.

The rock here also appears dominantly tuffaceous, with beds of gleaming white diatomite and black lignite.

Photo unprocessed. August 18, 2011. FlashEarth location (Cross-hairs on pull-out. The high tension power lines are the landmark to look for, here- this is the main conduit for taking Columbia River hydropower to California.). If you choose to visit this spot, please see Monday's safety comments; as I commented above, we chose not to cross here.

I had never stopped here before, and I don't think I'd even noticed how great this road cut was, despite having passed somewhere around 15-20 times over the years. It actually was a very fortuitous stop, because Dana had never seen Basin and Range consciously, so I was able to use the structures exposed here to introduce her to the structures we'd be seeing on a much grander scale over the following couple days.

The rock here also appears dominantly tuffaceous, with beds of gleaming white diatomite and black lignite.

Photo unprocessed. August 18, 2011. FlashEarth location (Cross-hairs on pull-out. The high tension power lines are the landmark to look for, here- this is the main conduit for taking Columbia River hydropower to California.). If you choose to visit this spot, please see Monday's safety comments; as I commented above, we chose not to cross here.

Thursday, January 17, 2013

Up-Goer 5

In homage to Randall Munroe's brilliant, now-classic, comic, Up-Goer Five, the Geoblogosphere's meme du jour is to write about what each of us does using only the 1000 (10 hundred) most common words in (I presume, American) English. The Up-Goer Five text editor makes the job pretty painless. Here's my entry:

Highly Allochthonous is keeping a running list, with new additions coming into the comments. So additions will be rolled into the list later this evening. If you haven't already, give it a shot!

Update, Jan. 18: Anne Jefferson and Chris Rowan have created a Tumblr, "Ten Hundred Words of Science," to archive all the terrific entries, which have come in torrents. And not just earth science, but across the board. Don't miss it!

I like rocks. Also high places that sometimes act like they're on fire. But what I really like is sharing what I know about rocks and high places, and how those things came to be. What made them? What moved them? Why are they the way they are? I think the answers to these questions are important, and I think people should know more about them. So I use words and pictures to show everyone how beautiful and amazing rocks and high places are, why they're important to us, and why it's important to know about them. Sometimes I even get to take people to see rocks in real life, which is the best part of what I do.When I saw the first example, from Anne Jefferson (@highlyanne) yesterday, I dismissed the exercise as frustrating, and very time consuming, as I expected to burn hours trying to find synonyms. But when I finally decided to give it a shot, it only took a few minutes- I probably spent more time on the second sentence than the rest of the paragraph, when I tried to find some way to say "volcanoes."

Highly Allochthonous is keeping a running list, with new additions coming into the comments. So additions will be rolled into the list later this evening. If you haven't already, give it a shot!

Update, Jan. 18: Anne Jefferson and Chris Rowan have created a Tumblr, "Ten Hundred Words of Science," to archive all the terrific entries, which have come in torrents. And not just earth science, but across the board. Don't miss it!

Geo 365: Jan. 17, Day 17: The Whole Cut

A final shot of the road cut shown over the last few days, showing most of the cut into these lacustrine sediments, looking roughly WSW down the grade. Tuesday's shot was taken from approximately where the oncoming truck is in this shot. Tomorrow we'll drive up the hill a bit, and see what this stuff looks like when it's been affected by Basin and Range style faulting...

Photo unprocessed. August 18, 2011. FlashEarth location (cross-hairs on pull-out). If you choose to visit this spot, please see Monday's safety comments.

Photo unprocessed. August 18, 2011. FlashEarth location (cross-hairs on pull-out). If you choose to visit this spot, please see Monday's safety comments.

Wednesday, January 16, 2013

Geo 365: Jan. 16, Day 16: Lignite

From the same spot as the last two days, a crumbling chunk of lignite. I interpret the sequence of yesterday's photo to be (from bottom to top) 1) a period of fairly intense ashy volcanism, with the ash washed into a lake by streams- it's clearly water carried, not ash fall; 2) a long period of quiescence, with fairly deep water, allowing mostly pure diatomite to settle out- the clastic contribution during this time must have been very low; 3) shallowing water allowed colonization by reeds and other grass-like water plants. These died and accumulated to form peat, which has been compressed and lithified to lignite; 4) Another period of more active volcanism, apparently becoming more mafic at the top of the section shown in yesterday's photo. Today's sample is a fragment that fell out of step 3, so to speak.

Photo unprocessed. August 18, 2011. FlashEarth location (cross-hairs on pull-out). Lens cap is ~52 mm. If you choose to visit this spot, please see Monday's safety comments.

Photo unprocessed. August 18, 2011. FlashEarth location (cross-hairs on pull-out). Lens cap is ~52 mm. If you choose to visit this spot, please see Monday's safety comments.

Tuesday, January 15, 2013

Geo 365: Jan. 15, Day 15: Lacustrine Sediments

Same outcrop as yesterday's showing a better overview of a lower portion of the pile. One of the nice things about this spot is that it's a fairly long cut, several hundred feet, and the grade is about as maximally steep as you'd want a major highway to be. As a result, you can walk through a very interesting sequence of lacustrine strata.

I'm not enough of a sedimentologist, I don't think, to have concluded that this is indeed a lacustrine sequence- I know I wasn't when I was told by Sharkey, on a sixty-five mile per hour reconnaissance drive-by, that that is what we were seeing. It's possible, however, that even if I hadn't known, finally stopping after many, many such drive-bys over the years (Mostly south-bound, with kids, neither of which made this a sensible stop), and looking carefully at the rock types for the first time, I might have come to the correct conclusion.

The buff and brown layers dominant in the lower portion and at the very top are tuffaceous silts and sands, with varying degrees of sorting. There are a variety of sedimentary structures, primary and secondary, in these layers. Primary structures include lots of cross-bedding, numerous cut-and-fill structures, and some ripple cross lamination. Secondary structures include all kinds of soft sediment deformation, including some ball-and-pillow structures. The bright white layers are diatomite, and the black is low-grade coal- I have been calling it lignite.

Now diatomite and lignite aren't "by definition" deposited in lake environments, but they strongly indicate it. Given the geography of this spot, utterly flat orientation of the bedding, and the looseness of lithification, I feel confident in saying this can only be a few million years old- Pliocene, maybe. So it can't be marine. It can't be fluvial, with that diatomite. What remains as a reasonable environment is lacustrine.

Photo unprocessed. August 18, 2011. FlashEarth location (cross-hairs on pull-out). If you choose to visit this spot, please see yesterday's safety comments. Also, this is pretty much non-geological, but might help you find the spot. This sign is at the lower end of the road cut. If you're headed south, you could go to one of these spots, turn back to the north, and hit the pull-outs from the safer direction.

I'm not enough of a sedimentologist, I don't think, to have concluded that this is indeed a lacustrine sequence- I know I wasn't when I was told by Sharkey, on a sixty-five mile per hour reconnaissance drive-by, that that is what we were seeing. It's possible, however, that even if I hadn't known, finally stopping after many, many such drive-bys over the years (Mostly south-bound, with kids, neither of which made this a sensible stop), and looking carefully at the rock types for the first time, I might have come to the correct conclusion.

The buff and brown layers dominant in the lower portion and at the very top are tuffaceous silts and sands, with varying degrees of sorting. There are a variety of sedimentary structures, primary and secondary, in these layers. Primary structures include lots of cross-bedding, numerous cut-and-fill structures, and some ripple cross lamination. Secondary structures include all kinds of soft sediment deformation, including some ball-and-pillow structures. The bright white layers are diatomite, and the black is low-grade coal- I have been calling it lignite.

Now diatomite and lignite aren't "by definition" deposited in lake environments, but they strongly indicate it. Given the geography of this spot, utterly flat orientation of the bedding, and the looseness of lithification, I feel confident in saying this can only be a few million years old- Pliocene, maybe. So it can't be marine. It can't be fluvial, with that diatomite. What remains as a reasonable environment is lacustrine.

Photo unprocessed. August 18, 2011. FlashEarth location (cross-hairs on pull-out). If you choose to visit this spot, please see yesterday's safety comments. Also, this is pretty much non-geological, but might help you find the spot. This sign is at the lower end of the road cut. If you're headed south, you could go to one of these spots, turn back to the north, and hit the pull-outs from the safer direction.

Monday, January 14, 2013

Sketched in Sand

I mentioned this on Twitter yesterday, but saw no reaction- no retweets or favorites- so I presume most of my geo-type followers missed it. And it's much too cool for me to let that happen. A friend e-mailed me the link to this site yesterday, and the story told by this picture (and many others) is really quite amazing...

So what do *you* see in the above design? Hmm?

I'm betting "seismogram" was not the first thing to pop into your mind...

So what do *you* see in the above design? Hmm?

I'm betting "seismogram" was not the first thing to pop into your mind...

Geo 365: Jan. 14, Day 14: Deformed Cross-Bedding

Cross-bedding in what I've been told is lacustrine sediment. The clastic material is clearly ash-derived. There is a lot of evidence of soft-sediment deformation in this road cut; the photo above is a good example.

Photo unprocessed. Lens cap, ~52 mm, in lower right middle. August 18, 2011. FlashEarth location (cross-hairs on pull-out).

A word of caution: Route 97 is a busy, fast and dangerous highway. The pull-out is plenty big enough to get well off the pavement- please do. Also, visibility is decent but not great- that is, both pedestrians and traffic can see each other pretty well. But I WOULD NOT recommend trying to stop here from the south-bound lane, coming downhill. (one downhill lane, two uphill lanes). If you choose to cross the road, be very attentive. There's a pair of stops we made in this area; here we crossed. At the second, we just felt it was unsafe. There's plenty to see from the other side of the road. If it looks dangerous, don't even try.

Followup: Messing around in Paint.net, decided to post a processed version to bring out the details more clearly.

Photo unprocessed. Lens cap, ~52 mm, in lower right middle. August 18, 2011. FlashEarth location (cross-hairs on pull-out).

A word of caution: Route 97 is a busy, fast and dangerous highway. The pull-out is plenty big enough to get well off the pavement- please do. Also, visibility is decent but not great- that is, both pedestrians and traffic can see each other pretty well. But I WOULD NOT recommend trying to stop here from the south-bound lane, coming downhill. (one downhill lane, two uphill lanes). If you choose to cross the road, be very attentive. There's a pair of stops we made in this area; here we crossed. At the second, we just felt it was unsafe. There's plenty to see from the other side of the road. If it looks dangerous, don't even try.

Followup: Messing around in Paint.net, decided to post a processed version to bring out the details more clearly.

Sunday, January 13, 2013

Sunday Funnies: Gossip Edition

"Ham Solo," Bits and Pieces

Bits and Pieces

Criggo

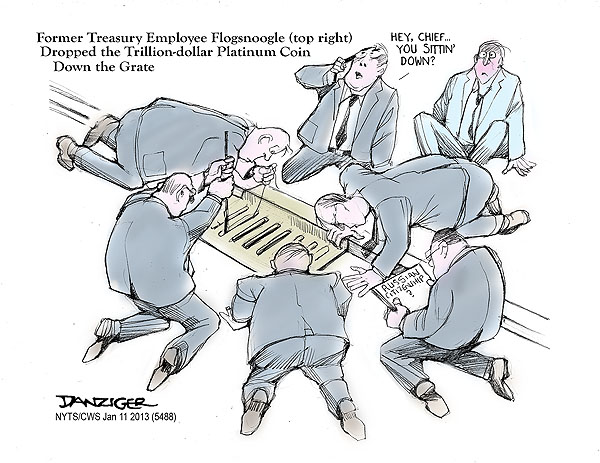

Danziger

Bird and Moon

Bird and Moon- I've posted this one before, but it's a classic.

"Going back to lab after winter break" Geology is Hard

Stupid Gifs

Married to the Sea

Bizarro

"Getting that one last rock sample out of the outcrop" Geology is Hard

Chuck & Beans

Sober in a Nightclub

Criggo

Bits and Pieces

AAAAAH! GETITOFFGETITOFFGETITOFF! Derpy Cats

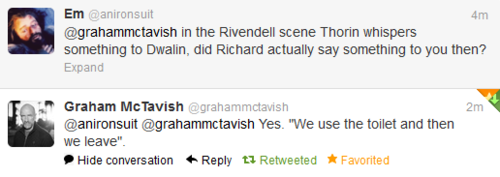

Wil Wheaton's Tumblr

Are You Talking to Meme?

Via 90% Unrelated

Tastefully Offensive

Clay Bennett

Cheezburger

"When someone thinks you can carbon-date Mesozoic rocks" Geology is Hard

Blackadder

Seismogenic Zone (Bill Nye, Neil deGrasse Tyson and Carl Sagan)

Sorry, gotta read most of the text to see the stupid, and reason for Criggo's title, "Sharpest Knife in the Drawer."

Tastefully Offensive

Buttersafe

"Returning to the lab after holiday" What Should We Call Grad School?

How 'bout that? Ham Solo near the top, Ham Solo near the bottom. Darius Whiteplume's Tumblr

Blackadder Until next Sunday, see you in the funnies... Bye!

Geo 365: Jan. 13, Day 13: Moar Pillows!

Same outcrop as yesterday's; four-pound hand sledge near lower left of the outcrop for scale. See yesterday's Geo 365 post for details and location. Photo unprocessed. September 20, 2010. Please click for full size. Delicious!